Daily Creative Arabia in conversation with Areen Hassan, a Dubai-based textile designer.

Article & Graphics by Rania Abdalla

Textile Artwear and Concepts by Areen Hassan

Textile Artwear and Concepts by Areen Hassan

Areen: Weaving Memory, Identity, and Infinity Through Textile

The Dubai-based artist was born in Jerusalem, and her work remains closely tied to her roots. Her practice is shaped by her upbringing and by a family lineage that traces back to Al Mashhad, a village in northern Nazareth. Areen grew up navigating stereotypes and the pressure to conform to a fixed idea of identity. From a very young age, she knew she wanted to study fashion, which at the time was the only creative field she was aware of. With limited resources and exposure, she had not yet encountered disciplines such as textile design.

As she grew older and gained access to the internet, her understanding of the creative field expanded. She discovered textile design and began to see it as a discipline that aligned more closely with how she thought and worked. She initially applied to study fashion design, then decided to shift into textile design once she realized it offered the conceptual freedom and experimental space she was searching for.

Today, Areen identifies as a textile artist and designer. She describes herself as being deeply drawn to concept design, textiles, experimentation, installations, and statement work. Her practice is grounded in material, structure, and meaning, rather than wearability or trends.

“I am more connected to concept design, experimentation and installations. I never felt that I had the vision of a fashion designer. I always had the vision of a textile artist.”

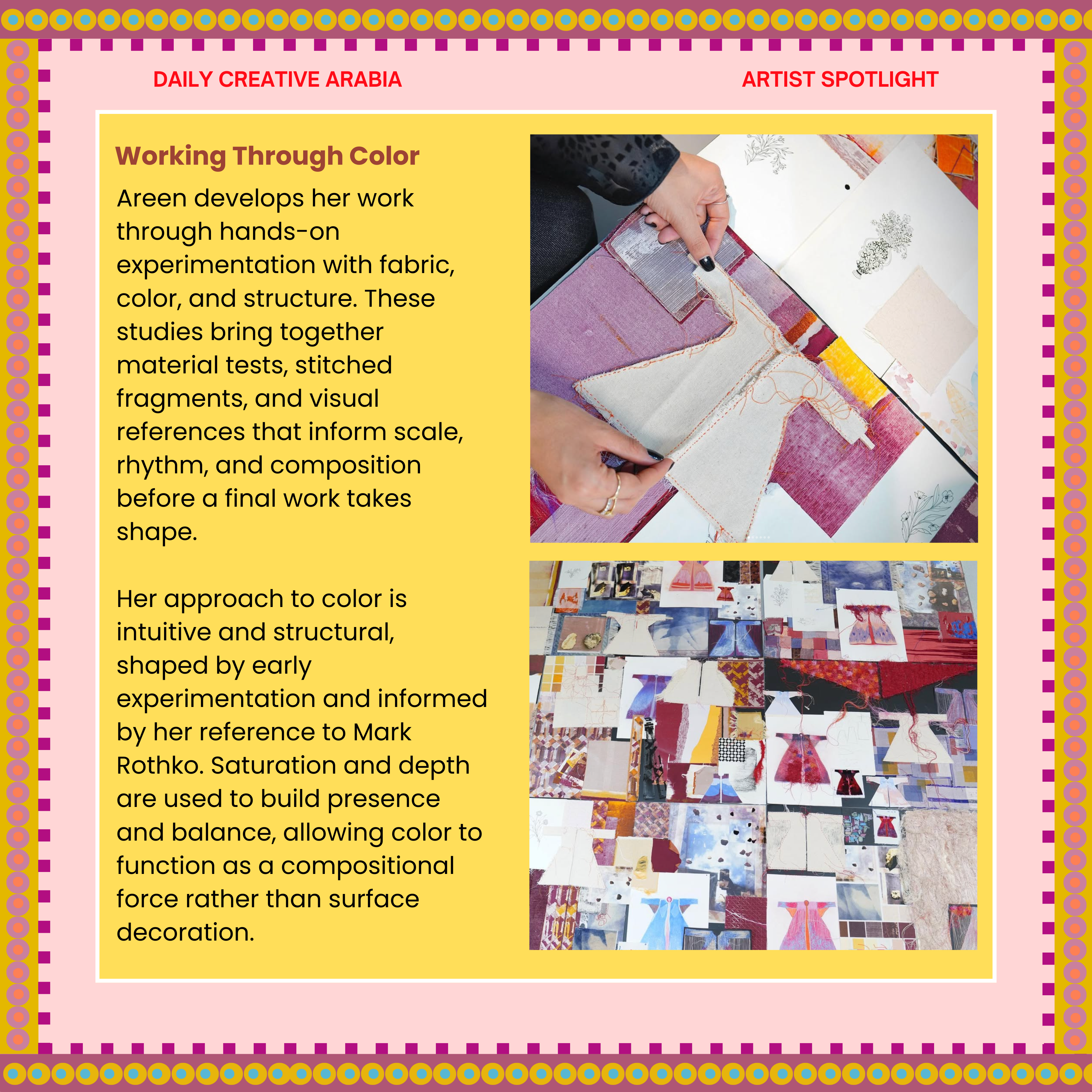

Color as Instinct and Reference

Even as a child, Areen worked instinctively with color, often creating combinations that felt unfamiliar to those around her. Her choices were questioned at the time, but those early experiments became the foundation of her visual language.

“I used to mix colors in a way people did not understand. Now I see that everything I do today started from those experiments.”

Her strongest reference point when it comes to color and composition is Mark Rothko. She is drawn to his use of saturation, depth, and emotional weight, and to the way color functions as presence rather than decoration. That influence continues to shape how she builds palettes and layers tone, using color as structure.

Unraveling Threads

Unraveling threads, or tanseel, is the act of unthreading fabric from within the weave rather than cutting it apart. In Areen’s work, the textile remains whole as its internal structure is revealed. The process exposes continuity, strength, and the systems holding the material together.

This approach runs through all of her work. It is not tied to a single piece or moment, but shapes how she thinks, designs, and works with material. Rather than relying on imagery or surface decoration, the fabric itself becomes the site where memory, identity, and resilience are expressed.

For Areen, unraveling threads became a way to talk about memory and endurance. “When you unfold fabric thread by thread, you return it to its origins,” she says. “Even though the dress becomes incomplete, the thread is still strong.”

Experimentation as a Philosophy

Experimentation sits at the core of Areen’s practice. She sees it as a necessary condition for growth, openness, and expanded vision.

She says, “When people experiment, they become open. The idea grows with them. Experimentation creates a bigger imagination.”

Her work brings together research, architecture, color, calligraphy and textile techniques. Through repetition, material, and structure, Areen treats textile as a living archive. “The more I work with textile, the more I grow, not only as an artist, but in how I understand my own practice. Each piece teaches me something new, and with every work, I become more certain about my voice.”

The Islamic Garden as Framework

One of the most consistent conceptual frameworks in Areen’s work is the Islamic Garden. While studying design, she became increasingly drawn to its logic. The symmetry, spatial organization, and intentional placement of elements mirrored how she already approached textiles.

In an Islamic garden, nothing is accidental. Trees create balance and shade. Water sits at the center, offering calm and continuity. Motifs repeat to establish rhythm and order.

Over time, Areen noticed parallels between the structure of Islamic gardens and Palestinian embroidery. Each region’s embroidery carries its own colors, patterns, and stitches. Every motif is shaped by place, history, and tradition.

“I found a language that connects both worlds,” she says. “The garden and the embroidery speak to each other.”

This connection became central to her first university project, a collection of twelve hand sewn pieces inspired by the Palestinian thobe. The work brought together Islamic garden logic and embroidery structure, forming a tribute to Islamic culture and Palestinian heritage expressed through textile rather than narrative.

Color, Contrast and the Statement of Materials

Areen’s work is often defined by warm, saturated colors. She gravitates toward tones that carry comfort, emotion, and presence rather than neutrality. Red, gold, orange, lavender, and indigo appear repeatedly across her designs, forming a consistent and recognizable palette.

She is intentional about how her pieces are constructed front and back. The back is left plain, while the front carries the work. One holds the foundation, the other the expression. Together, they create balance.

Sleeves also carry symbolic meaning in her practice. Long and short sleeves exist in relation to one another, not as opposites but as complements.

“When I put the sleeves together, they complete each other,” she says. “It is the idea of Al Kamal. Wholeness.”

All of Areen’s pieces are hand-dyed and made using natural materials, especially silk, which she values for its ability to absorb and reflect color with depth and luminosity. Sustainability is central to her approach, and every piece is handmade and unique.

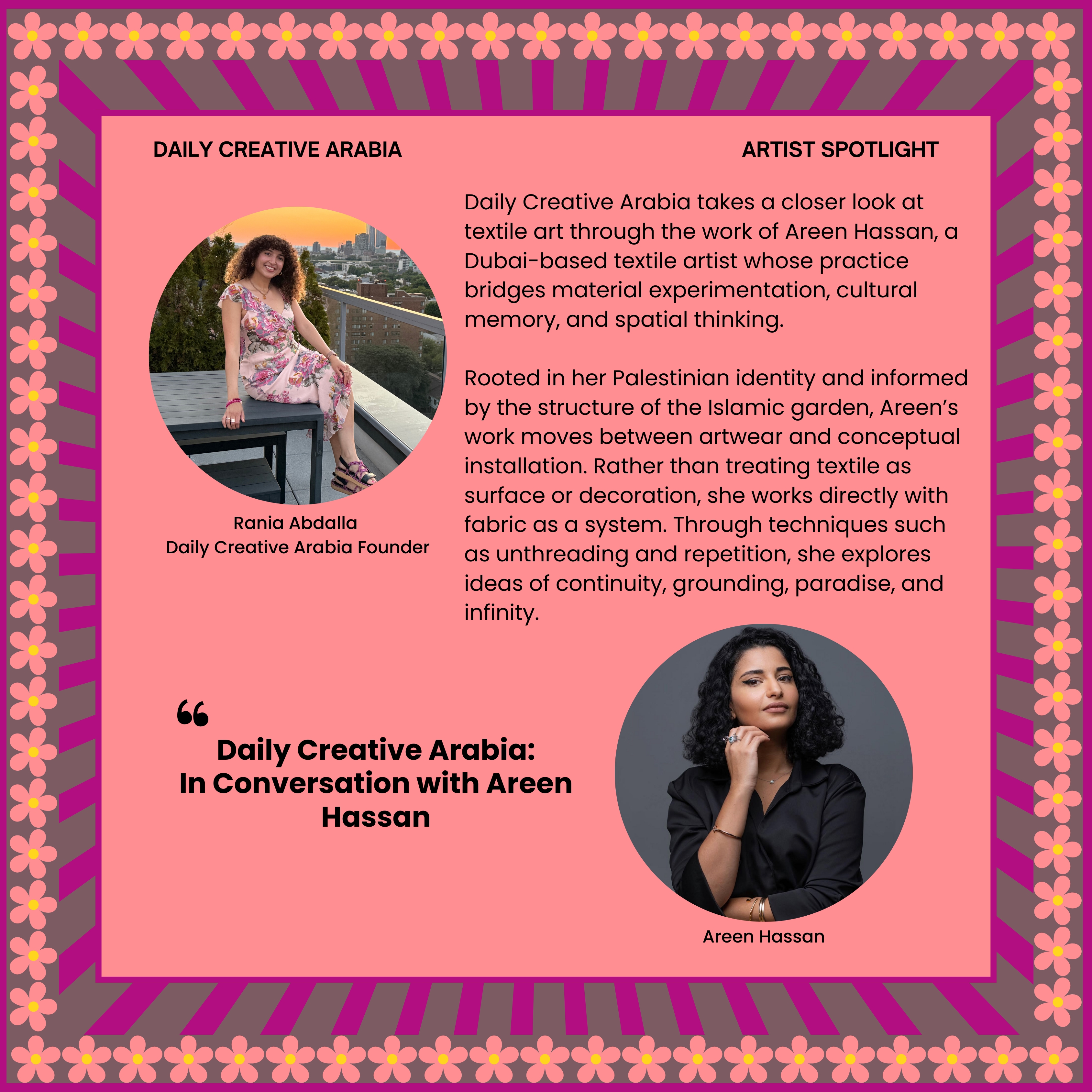

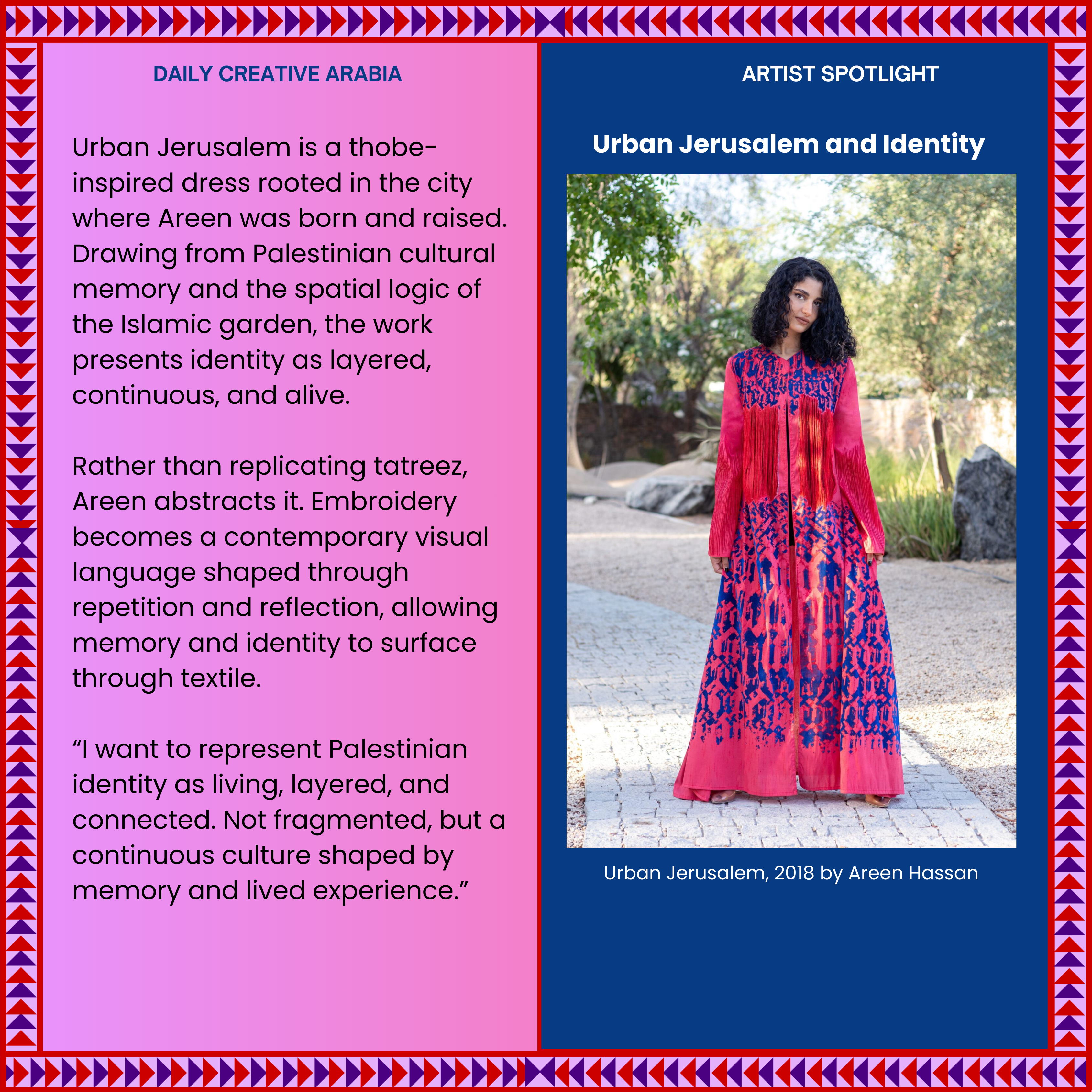

Urban Jerusalem

One of Areen’s earliest and most defining works, Urban Jerusalem is a thobe-inspired dress that brings together Palestinian cultural memory and the spatial logic of the Islamic garden.

Created during her college years, the piece is named after the city where Areen was born and raised. Growing up in Jerusalem shaped her early visual memory and understanding of culture. The work responds to simplified representations of Palestinian identity, offering instead a vision of Palestine as continuous, layered, and alive.

The cut and structure draw from the Palestinian thobe. Areen references a historic indigo-dyed thobe, which became the foundation for the royal indigo pattern used in this work. The garment was hand sewn and never tried on. Its oversized scale shifts the focus away from wearability and toward concept and form. At a later stage, the dress was cut from the bottom, altering its silhouette and distancing it from traditional construction.

Color plays a central role in how memory and identity surface in the piece. Red appears as the first color she works with, rooted in Palestinian embroidery and visual culture. For Areen, red carries emotional and historical weight.

“Red is strength to me,” she says. “It is presence. It is emotion.”

Rather than replicating tatreez, Areen abstracted it. The embroidery begins in red and expands into additional colors, transforming tatreez into a contemporary visual language. Mirrored panels create a sense of reflection and continuity, while repetition draws from the logic of the Islamic garden, where pattern establishes rhythm and infinity.

When our conversation turns to identity, I ask Areen how she wants to represent Palestine to an international audience. Her answer is clear.

“I want to represent Palestinian identity as living, layered, and connected. Not broken, but a continuous culture shaped by memory, beauty, and resistance.”

In Urban Jerusalem, unraveling threads becomes especially visible. The act of unraveling is not a form of loss, but a return to origin. A way of holding structure, memory, and identity together.

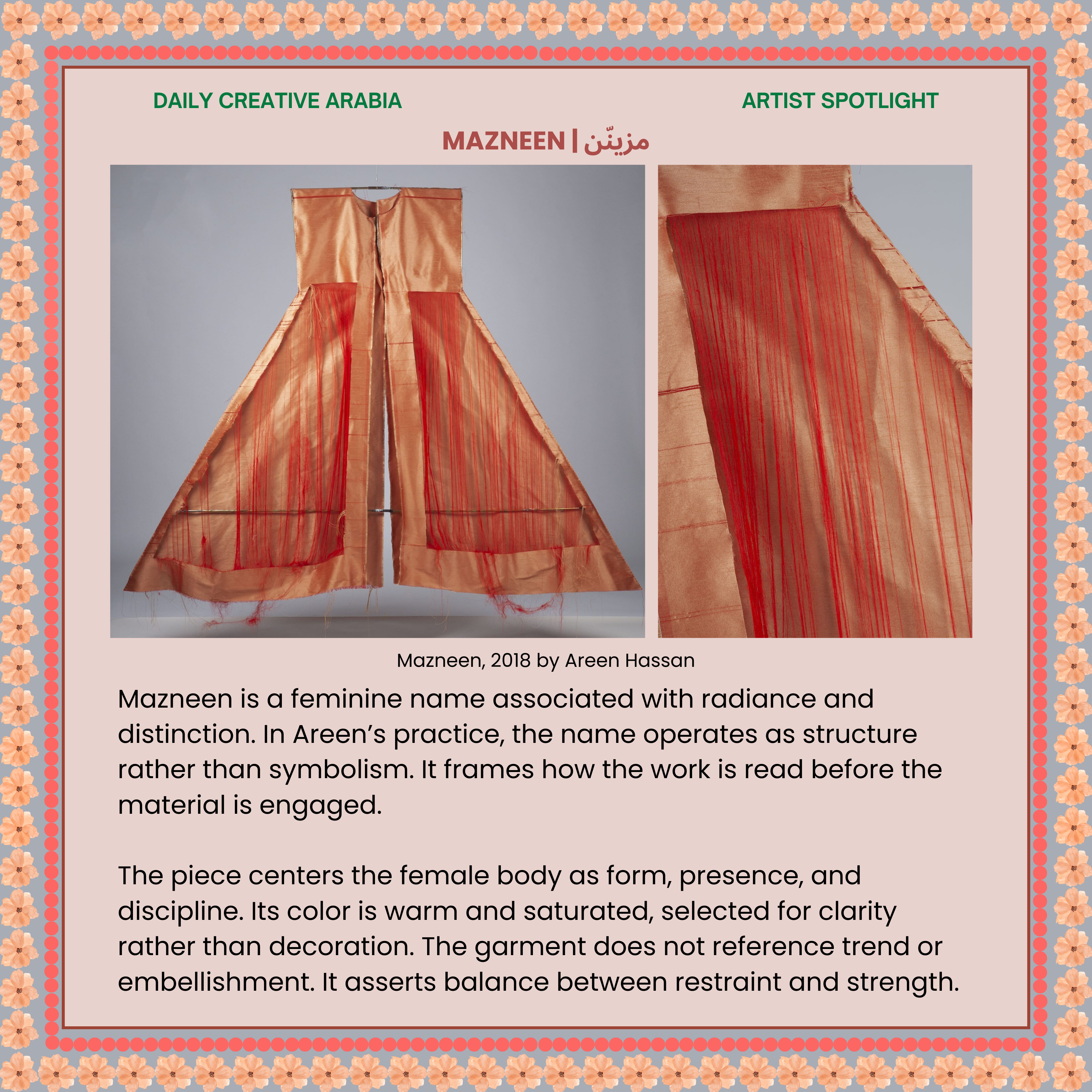

Mazneen

Mazneen is a feminine name associated with glory and shine. In Areen’s work, the name introduces language, memory, and presence before the fabric is seen. The piece reads as a declaration of womanhood grounded in faith, strength, and luminosity.

Across her practice, Areen assigns Arabic names to her works before the making begins. The names are rooted in Middle Eastern culture and function as conceptual anchors rather than descriptive labels. “The name comes from the concept,” she says. “It guides the whole work.” Each design carries its own emotional and conceptual identity, shaped by language as much as by material.

Through Mazneen, Areen shifts her focus away from trend or season and toward material, color, and surface. The fabric becomes a site of emotional and cultural expression, grounded in warmth, luminosity, and presence. The names of her conceptual dresses consistently reflect aspects of her identity and cultural memory.

Paradise and Islamic Garden

The Paradise Dress, part of her Islamic Garden body of work, translates these ideas into form through repetition and balance.

“I wanted it to carry a spiritual indication,” she says. “Something that reminds you of paradise.”

Alongside Urban Jerusalem and Mazneen, The Paradise Dress was acquired by the MKG Museum in Hamburg and is now permanently displayed as part of its Islamic collection.

How Areen Imagines the Portrayal of Paradise

One of the central installation works from this period is The Portrayal of Paradise, a four-and-a-half meter blue textile piece built around the concept of infinity. Inspired by the Islamic garden, the work approaches paradise through movement rather than stillness.

The pattern is formed through continuous repetition. A blue and white central element sits at the core of the installation, while threads extend outward like flowing water. The surrounding pieces act as reflections, echoing how water mirrors the garden around it. Repetition becomes a visual language for infinity, belief, and the desire to reach something eternal.

“The idea is that the pattern keeps repeating itself, which is how I express infinity” she explains.

For Areen, paradise is an iconic idea that people carry with them throughout their lives. It exists not only as a place, but as a motivation. People grow up imagining paradise and are driven by the idea of reaching it in the afterlife and experiencing that state of being.

When asked which element of the garden she identifies with most, she answers immediately.

“I would be the water. Water represents infinity, continuity, and movement. It never stops. It finds new paths. That is how I see identity and how I see my work.”

Hanging Threads through the Heavenly Loom

In Heavenly Loom, Areen extends her textile practice beyond the body and into space. The work is presented as a suspended installation, designed to remain in motion rather than exist as a fixed object. During exhibitions, the threads are positioned beneath air circulation, allowing them to shift continuously.

The installation follows the spatial logic of the Islamic garden, where structure is formed through repetition, flow, and directional movement. Layers of pink and red threads hang in parallel, creating depth and continuity as they respond to air and light.

“Water never stops,” she says. “It moves in every direction. I wanted the installation to feel the same way.”

Here, air replaces water as the activating force. Movement sustains the work, and repetition becomes its organizing principle. The threads never settle. The installation unfolds through motion, forming an environment shaped by rhythm and time rather than fixed form.

From Carpet to Abaya

The Woven Self originates as a carpet. Rather than constructing a garment, Areen worked directly with a single woven carpet and began unraveling it from within. She did not cut the material at any point.

“I didn’t cut the fabric at all,” she says. “I unthreaded it and shaped the dress from what was already there.”

Through a careful process of unthreading, she loosened and reshaped the existing weave until the carpet gradually took on the form of a dress. The textile remains whole throughout the process.

“For me, the fabric stays whole,” she explains. “The form comes from opening it, not breaking it.”

What emerges is not a dress made from fabric, but a dress revealed from a carpet. This method reflects the logic of the Islamic garden, where form is shaped through flow, repetition, and internal order rather than division or fragmentation.

“Unthreading doesn’t mean weakness,” she adds. “It shows what is holding everything together.” In simpler words, “the woven self means you are the sum of everything that has crossed you, and you still hold together.”

The piece exists simultaneously as carpet, garment, structure, and landscape.

Don't miss out on the latest from Areen Hassan - make sure to follow her on IG @by_areen.